Revolutionary Tennis |

||

Tennis Instruction That Makes Sense |

||

EVIDENCE IT IS NOT A MYTH

©10/2008, Mark Papas I'm sure you figure you snap your wrist on the serve on purpose and that pros do as well. But you may be confused by either of two pundits and their followers who tell you you're not figuring things out correctly here. One, Vic Braden, claims you and pros aren't snapping the wrist but only pronate the arm and hand; the other, John Yandell, says wrist movements are "passive," "not a causative factor" in power and spin, and that the wrist moves merely because it is "along for the ride" due to the movement of larger muscle groups or body parts. Both groups call the wrist snap "a myth." This point of view is nothing short of ridiculous. Revolutionary Tennis says you're the one figuring things out right. And now clear scientific evidence disproving these pundits exists and can not be ignored.

TENNIS IS SIMPLE TO UNDERSTAND

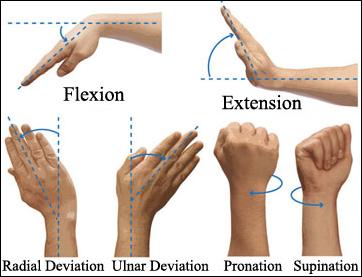

Is wrist movement a conscious thing, known as a muscle-driven joint torque, or is it involuntary, known as a motion-dependent torque because other body parts are moving? Pundits only claim the one, but Brian Gordon found both: He also found wrist movements to be conscious. What pros call a wrist snap is causative, active, purposeful. Strike One. These science papers on the serve show this voluntary, conscious wrist movement on the serve is also responsible for racket head speed. Since racket head speed leads to power this eviscerates the much narrower argument "the wrist snap for power is a myth." Strike Two. Brian Gordon's "The Serve and Tennis Science" clearly shows the % contribution of wrist movement on a serve, a.k.a. extension, deviation, flexion. The numbers show the wrist contributes second in global usage only to the twisting of the trunk, yet ahead of elbow extension, shoulder movement, upper arm twist and forearm pronation. Clearly the wrist is doing something. And Strike Three. There's much too much going on with the wrist to think it works as an afterthought, uncontrollably. There are 6 papers Brian Gordon has written: "The Serve Wind Up," "Upward Swing Part 1 and Part 2," "The Serve Back Swing: The Upper Body," "The Backswing: Part 1," and "The Serve and Tennis Science." And more to come, no doubt.

Now for the facts. Brian Gordon based his technique from other researchers who had studied various body segment motions from volleyball and tennis. He did his own expanded analysis and studied "nine NCAA Division I players, measuring how the motion of each segment of the body contributed to the speed of the racquet head." He broke this down into 5 body segments.

He determined "the contribution from each segment (or associated joint action) every 1/100 second from the racquet low point to just prior to contact," and he "summarized the results at three key points in the motion." These three key points are:

I have taken the % values from each of the 3 key points in the motion (A, B, C) and listed them in order to give an overall look at the percentage contributions of each of the 5 body segments. The author emailed me to say he did not do this on purpose because they are "instantaneous contributions which may, and do, have negative impacts in other parts of the swing" and because "assigning overall contribution (or combining different rotations at a joint like the wrist) can over-state or under-state their global importance and de-emphasizes the processes by which these contributors are integrated and prepared - in my opinion - however I provide the data so readers can draw their own conclusions." It turns out the twisting of the trunk had an aggregate 27% involvement in the serve over these three key points in the motion, and the wrist was second with 24%. So draw your own conclusion, see how this lays out for yourself. You will note some values at a particular point add up to more than 100%, and it is "because other segment motions contributed negatively [and] that a negative contribution may be necessary for a segment to correctly position itself or to contribute to the positioning of other adjacent segments."

Twisting of Trunk seems to me just that, and from reading Brian Gordon's paper you do the archer's bow, you lean back a bit, all in the name of developing forward angular momentum.

Shoulder Movement is more complicated. It involves the cartwheel, shoulder abduction (lift the upper arm at the shoulder joint) requiring external shoulder rotation, shoulder joint motion that leads to upward and forward upper arm movement. External, then internal shoulder flexibility is the holy grail here.

"And indeed, wrist flexion is a major contributor to racquet speed near and at contact. The significant portion of this flexion is caused by active and conscious muscular contraction and associated joint torque." ["Upward Swing Part 2"]

Throughout his expanded analysis Brian Gordon points out that while people studying this "don't as yet fully understand the origins of all the joint forces," and that "every player will use his own combination of muscular contraction (joint torque) and joint forces (motion dependent torque) to rotate the segments of the hitting arm," he nevertheless states there is active, conscious movement of the wrist by muscular contraction. Mr. Gordon's work reads as a sincere, honest effort and is to be commended, he is one of the good guys. But forget about looking at the wrist snap within the narrow context of only power or racket head speed, these are red herrings because the wrist is involved in so much more. The use of the wrist is directly related to the spin on the ball, to the upward swing path, to the swing pattern, to the racket position at the end of the drop. And all of this stuff prior to contact is a conscious effort. The icing on the cake is the conscious nuclear pop at the end. There are indeed more strikes to be called against those shouting "myth" because it is intellectually dishonest and professionally irresponsible to claim an either/or, black/white scenario of what dominates kinetic contribution at a joint: only a muscle driven joint torque or only a motion depended torque? That is, if a motion dependent effect is dominant it should not be interpreted as a lack of conscious contraction, and vice versa, because both will be present, both will contribute (as the author indicated to me). Furthermore, there is a lot of crosstalk going on between relaxation and contraction and of allowing motion dependent effects to occur, issues that science now admits it knows little of but of which athletes are aware and amateur analysts can not imagine.

Let's be clear: you snap your wrist. On purpose. 3-dimensionally, not in a bye-bye motion.

You do snap your wrist on purpose, this snap does contribute to power, but you can't get a powerful serve by only snapping your wrist. To have more power and avoid injury you use more of your body and I think you know that because tennis players are a smart, independent bunch. And like Brian Gordon, those offering tennis instruction need to speak up to tennis players. Now when does this "wrist snap" happen within the symphony of moving body parts? At the last millisecond right before you hit the ball? At the moment you hit the ball? Is it a last ditch effort? Of course not, you know that, it happens very much before you ever hit the ball, like turning the wheels of your car before you're in the middle of the curve. If you bring your racket head uP to the ball and "snap" the moment you hit you merely hit down on the ball. What pros call "snapping the wrist" is a process that begins much earlier than right before the moment you hit the ball. You don't reach up to the ball with the racket and then consciously snap the wrist at contact, by then it comes to the party too late.

Perhaps the rub is that our tennis pundits view only contraction as "the" conscious muscle effort whereas athletes and true Biomechanics scientists also know relaxation to be conscious effort. Being able to relax the hand and wrist allows one to train the arm to perform its myriad operations in a serve, allows the racket to be placed optimally during the swing path, and ultimately sets the stage for the wrist to jump through its hoops when required. If you tense up the wrist this can not happen. Mr. Gordon notes, "During the mid portion of the upward swing, wrist ulnar deviation takes over as the most important wrist contributor to racquet speed....This ulnar deviation is not caused by conscious contraction. It is driven primarily by joint forces and their motion dependent effects." To allow for wrist ulnar deviation material to "racquet speed" to be "driven primarily by joint forces and their motion dependent effects" means the wrist and hand can not be rigid. Thus the sound advice of a loose grip, spaghetti arm, etc., on the serve, advice that is heeded consciously throughout the swing. Contraction of the wrist is most pronounced when flexing, not deviating, thus the difficulty in measuring how much contraction is associated with deviation. Even if you choose to argue a zero contraction effort associated with ulnar deviation nevertheless a relaxation effort is associated with it. And this is done purposely. As you're bringing the butt cap uP to the ball your consciously loose/extended/radially-deviated wrist begins the process of "snapping." The now-documented conscious flexion that "is a major contributor to racquet head speed near and at contact" shows the climax of a process that began first with a loose grip and spaghetti arm, then added radial deviation and extension at the low point and then ulnar deviation in the mid portion of the upward swing. AVOIDING THE DEADLY WAITER'S TRAY POSITION

The student who loads the body can not get the snap unless the wrist is used in a particular manner or is allowed to be used in a particular manner prior to dropping the racket down behind the back; the student who does not place the wrist in the proper lift-off scheme prior to swinging uP will not enjoy the proper uPward swing path; the student who can not relax the wrist and allow for wrist radial deviation before and while swinging (the butt cap) uP will not only succumb to the deadly waiter's tray position but also fail to enjoy the tail-of-the-whip effect the wrist can apply at the end. [Sampras sequence, second column from left, shows this wrist radial deviation occurring, and it occurs only as a result of having learned to do it and not because the elbow pops up. The elbow pops up not on its own, it pops up because of what the hand is doing at this point. The elbow is not the trigger for the hand/wrist, the hand/wrist movement is the trigger for the elbow.]

So there we have it, you've been right all along. There is a wrist snap, or a snap of the wrist, and it's done on purpose; it is real, it is added to the pronating arm and hand. Tennis is simple to understand, though it can be hard to do per your wants and desires. Temper those desires a bit, i.e. relax, and you'll surprise yourself by doing better than expected. TRUST YOUR INSTINCTS. REFUTE HEGEMONY. FREEDOM.

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A former teaching pro-now-Ph.D. candidate Brian Gordon in a series of articles researching "power" on a serve has published on the question whether the wrist moves voluntarily/consciously as a result of a muscle contraction on a serve ("wrist snap"), or whether the wrist moves involuntary because it is "along for the ride". This series of scientific articles ironically are showcased on Yandell's prominent web site which screams "the "wrist snap" "is a myth" in his article, "The Myth of The Wrist: The Serve." I stumbled onto Gordon's "The Serve and Tennis Science" by an email blast from the USPTA, I never would have found it trolling the site.

A former teaching pro-now-Ph.D. candidate Brian Gordon in a series of articles researching "power" on a serve has published on the question whether the wrist moves voluntarily/consciously as a result of a muscle contraction on a serve ("wrist snap"), or whether the wrist moves involuntary because it is "along for the ride". This series of scientific articles ironically are showcased on Yandell's prominent web site which screams "the "wrist snap" "is a myth" in his article, "The Myth of The Wrist: The Serve." I stumbled onto Gordon's "The Serve and Tennis Science" by an email blast from the USPTA, I never would have found it trolling the site. Relaxation is an integral part of an athlete's execution, it is done purposely as a conscious effort. Rebecca Soni of USC in an upset won gold in the 200 breaststroke in the 2008 Beijing Olympics and said, "It just kind of flowed. It just kind of happened. It felt great. I just tried to stay relaxed and not rush through the water and keep my stroke strong, and just power it through the end." This can also be said of our serve: you will flow, it kind of happens, and we try to stay relaxed, not rush through the body set-up and swing path, keep the body strong and then power it uP to the ball and go nuclear with the wrist at the end.

Relaxation is an integral part of an athlete's execution, it is done purposely as a conscious effort. Rebecca Soni of USC in an upset won gold in the 200 breaststroke in the 2008 Beijing Olympics and said, "It just kind of flowed. It just kind of happened. It felt great. I just tried to stay relaxed and not rush through the water and keep my stroke strong, and just power it through the end." This can also be said of our serve: you will flow, it kind of happens, and we try to stay relaxed, not rush through the body set-up and swing path, keep the body strong and then power it uP to the ball and go nuclear with the wrist at the end.