Revolutionary Tennis |

||

Tennis Instruction That Makes Sense |

||

Step 12 The Tennis Serve Part 4: The Upward Swing: The Flight Of The Tennis Racket Before we can fly we first need to talk about the elephant in the room. When you hear or read about the back scratch on a serve, what does it mean? Is it real, or is it a myth? If you hold a pencil above your head and I mention the two words back scratch to you I bet you would reach down behind your back with the pencil. Now with this same pencil down behind your back, if I mention the words back scratch would you throw the pencil up to the ceiling?

Vic Braden keeps telling us to: "forget the back scratch... the worst thing you can tell a player learning to serve is, "Get your racquet down behind you and scratch your back,""..."you should not try to lower it [the racquet] in an attempt to scratch your back." (all in TENNIS magazine, 1989). In 2001 in Tennis Week magazine (tennisweek.com) he believes it is a "myth" for the "tennis server...to scratch his back...while reaching upwards with the racquet." Racquet down and scratch your back, scratch your back while reaching up with the racquet.... Confusing, and then declaring the whole kit and caboodle "a myth"? Fire and brimstone! [If you want more on this tontería please click here.]

NO CONFUSION

The racket never touches the back on the way down or up. And there is absolutely no way this metaphor developed to help you swing up on the serve because everyone knows that swinging up is similar to throwing a ball. That's the metaphor we use for the upward stroke, UP like throwing a ball. What would you say to the student to avoid the waiter's tray problem, "salute" with the racket? Gimme a break. There is no fight or misunderstanding in the greater tennis world over when and where and why on the back scratch for the serve. It's for getting the racket both behind and down the back James Dean was an actor, Jimmy Dean is a sausage. Buh-bye elephant.

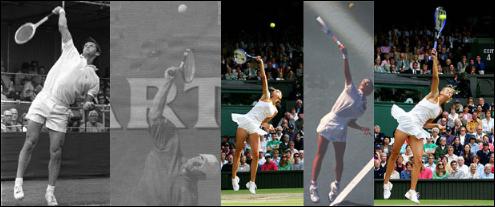

RACKET ARM BALLET Our tennis arms look kind of funny, or odd at times when we serve, don't you think? There's this bending of the wrist, relaxing of the arm, the coordinated drop and lifting of both arms, spreading the chest, separating the arms, keeping them together. The racket seems to be held lightly in a pro's hand and yet it moves up faster to the ball than Billy the Kid's gun leaving its holster. It's balletic, and there's a choreography to it, but first the reason for this form. AERODYNAMICS > ACCELERATION > POWER Acceleration is power, and pros make the tennis racket fly on a serve by moving it through the air on its edge for as long as possible before hitting the ball to minimize drag. Only just before contact does the racket face actually turn to face the ball. The dreaded waiter's tray scenario will short-circuit this process and abruptly grounds the stroke. Of note, all other strokes encounter wind resistance during their setup and forward stroke, thereby necessitating a certain degree of strength to move the racket fast. On a serve we get a break, we can make the racket slice through the air by moving it on its side. Which is why the serve set-up seems effortless. In the montage below I have a white piece of paper attached to one side of my string bed, facing you, and a red piece of paper to the other side, the hitting side. Reading from left to right, I draw the racket down like a pendulum, the racket slices through the air (Andy Roddick notwithstanding). I bring the racket back and up on its edge as much as possible and you now see the red piece of paper on other side of the string bed, I executed a small turn in the hand which turns the racket face. This turn of the hand is minimal and leaves the racket on its edge again so it points up to the sky -- OR you can keep turning the hand and (incorrectly) lay the racket back in the waiter's tray position. If you lay it back future acceleration is lost, as well as your ability to impact spin designed to help the ball dive down into the service box.

It's as if your racket were an ax or a tomahawk and you're going to drive the edge into the ball but at the last minute you change your mind and hit it with the flat face. Actually practice trying to hit the ball with the edge of the racket first, a little tomahawk style, and then later do the same but open it at the last minute.

THE WAVE

Think racket up on its edge, down behind the back on its edge, and then up on its edge. Though a pro most likely developed his serving motion in the womb, point is your hand needs to perform this waving maneuver if you want the racket to fly. As a historical note, perhaps this is the main reason why the game of tennis has always been associated with the elite. This waving maneuver is essentially the royal wave as performed so brilliantly by the members of Britain's House of Windsor. Which begs the question, which came first, the tennis wave or the royal wave?

LEARN TO AVOID THE WAITER'S TRAY Stand 6 inches away from the fence and with your back to it like I'm showing below in the photo sequence. Do the "down together, up together" with the arms and notice how your racket bumps into the fence behind you (photo 3 left to right), it's acting as a vertical plane to prevent your racket from laying back in your hand (waiter's tray position). Practice this to develop the muscle recognition, at times sliding the racket down behind your head and down the back behind you.

The idea is to control and redirect the racket's momentum away from laying back behind you (into the fence) to keeping itself even with your body (away from the fence). It's as if your intent were to make a circular motion in front of your body with the racket arm (two photos right) but of course it goes down behind your back.

Your hand and arm are in control of where the racket's going, the racket is not in control of your hand and arm. No Dr. Strangelove tennis rackets here please. OVERKILL My generation was taught to throw old, heavy wooden tennis rackets over the net to develop the serving motion. It's not easy when you're a kid to launch 14 ounces over the net from the baseline, but you could if you turned the racket on its edge, broke the wrist, and threw up. Throwing, and up, is the analogy for the upward swing. I think too often students merely swing the racket with just-enough acceleration to get the light and small ball over the net. Something is missing in your approach to the stroke. Throwing a heavy racket over the net as a kid taught me that swinging the hell out of the racket was primary, the hitting of the ball was secondary. The Holy Grail to the serve is swinging as all get-out. Overkill. Bring the elephant gun to kill the ball. Swing more than it would take to merely get the ball over the net and into the service box at a decent pace, puh-leeze! Don't worry, the ball will go in when you change the swing trajectory, change the grip, and use your wrist and arm better during the contact (upcoming). But-you-need-to-swing! At-the-dod-gamned ball! Come on! Once I could easily throw a wooden racket over the net and serve relatively hard my tennis coach François Savy taught me a racket acceleration drill that really pumps you up.

THE LOOP: 2 BEATS

Here's the second quicksand trap on a serve. First is the weight shift, second bending the arm too quickly, third the waiter's tray thing. Too often tennis aficionados will have their arms go "down together, up together" but then immediately fully bend the racket arm. You (toss and) fully cock the arm while the ball's still going up, leaving the arm motionless. Effectively you've lost the springing potential of the arm, much like on a groundstroke if you drop the racket too early and the arm waits, dead weighted, with the "racket back." While there is a continuous motion of the racket arm the continuous motion is not at the same speed. This distinction between the serve's two beats on the loop means acceleration. Often this distinction makes it seem there is a pause, or a stop, in the serve motion, but there isn't. There is a pause only when the toss is way too high. All pros have a continuous motion with the racket arm, the exceptions are few, but no one keeps the same uniform speed throughout. For the fundamentally minded, when the racket goes down behind the back and then up to the ball the racket makes a looping motion of sorts behind the back, like a number 8 but missing half of the top circle. It doesn't go literally straight down and then straight up as if it were an elevator, but describing this small quasi looping motion to students doesn't seem to affect them in a positive manner. This motion is a no-teach thing, it comes all too naturally and if you point it out it gets confusing. Describing the bigger picture of the overall rhythm of the serve as a loop with two beats similar to a forehand proves beneficial. BUTTS UP

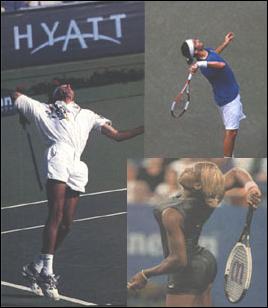

There you have it. The loop, the wave, the backscratch, the butt cap, and overkill, all designed to help you throw the racket up at the ball as aerodynamically as possible throughout to maximize racket acceleration. That's why we do that funny ballet thing with the racket arm, it keeps the racket on edge. Two things to avoid: the waiter's tray and bending the arm too soon. If you can your timing and swing will grow into itself. The toss arm goes up softly, fully, the racket arm has to get the racket up, then down the back and accelerate up to the ball. How best to do this? Toss the ball higher to have enough time for it all, which means you avoid the just-high-enough toss. See how it all ties in? Geez, there he goes again... Next up: The Incredible uPness of Contact: Using the body to hit the ball better. Thanks. [Photo credits: Backscratch: Stich, TENNIS magazine, 11/93, Stephen Szurlej/TENNIS magazine; Federer, USTA newsletter, Vol. 7, no. 1/2005; Serena, LA Times, 08/27/02, Agence France-Presse. Edge: Emerson, uncredited from web site; Roddick, Inside Tennis, 07/05, Getty Images; Sharapova, uncredited from web site ; Graf, TENNIS magazine, 05/97, Stephen Szurlej/TENNIS magazine. Loop: Ivanisevic, TENNIS Magazine, September 1996, Stephen Szurlej/TENNIS Magazine. Praying Mantis: Roddick, LA Times, 1/18/05, Greg Wood, Agence France-Presse, Getty Images; Venus, Tennis Week, 6/27/02, Art Seitz; Sampras, USTA newsletter, Vol. 7, no. 1/2005; Agassi, uncredited from web site. Butt cap: Serena, TENNIS magazine, 06/99, Mary Schilpp/CLP ; Rusedski, Rios, Ivanisevic, USTA newsletter, Vol. 4, no. 1/2002.] |

||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unfortunately students are confused regarding this simple how-to metaphor, and confused students leave the game. The loud voice behind this confusion is a licensed psychologist, self proclaimed tennis scientist, and one of our most esteemed celebrity tennis teachers.

Unfortunately students are confused regarding this simple how-to metaphor, and confused students leave the game. The loud voice behind this confusion is a licensed psychologist, self proclaimed tennis scientist, and one of our most esteemed celebrity tennis teachers. The back scratch metaphor developed to help you drop the racket

The back scratch metaphor developed to help you drop the racket

The racket moves into the back scratch position if you avoid the waiter's tray. The racket face slides back behind my head, the knuckles of my racket hand move towards my ear and head, the racket face is not turning or laying open (you see the red paper side). The racket drops down in a tear drop fashion behind my back and it is here, one more time, that the dreaded waiter's tray move must be avoided. To be successful the racket comes up from behind the back on its edge, you now see the white piece of paper on the non hitting side of the racket, you don't see the red. It is only at the end the racket opens up/faces (red side) to hit the ball (illustrative in my example, the racket turns sooner, see Graf right below).

The racket moves into the back scratch position if you avoid the waiter's tray. The racket face slides back behind my head, the knuckles of my racket hand move towards my ear and head, the racket face is not turning or laying open (you see the red paper side). The racket drops down in a tear drop fashion behind my back and it is here, one more time, that the dreaded waiter's tray move must be avoided. To be successful the racket comes up from behind the back on its edge, you now see the white piece of paper on the non hitting side of the racket, you don't see the red. It is only at the end the racket opens up/faces (red side) to hit the ball (illustrative in my example, the racket turns sooner, see Graf right below). The waiter's tray can also happen out of the back scratch position if the hand opens the racket face first and then you lift it up, photo right. Instead, lift up first on its edge.

The waiter's tray can also happen out of the back scratch position if the hand opens the racket face first and then you lift it up, photo right. Instead, lift up first on its edge. I include some photos of pros where you can clearly see how the racket remains on its

I include some photos of pros where you can clearly see how the racket remains on its  To keep the racket on edge during the swing the hand does a waving maneuver. The hand doesn't lay back like shooting a basketball to shoot the racket face to the ball, if it does you are doing the waiter's tray thing. The hand instead waves back and forth to wind up and then throw the racket in the same manner as if pitching a baseball. The third source of serve weakness for most tennis aficionados, the first being shifting your body weight backwards when the arms go down together and up together, second bending the racket arm too soon, is opening the racket face way early. You need to keep the racket on edge for as long as possible, and you open the racket face only right at the end.

To keep the racket on edge during the swing the hand does a waving maneuver. The hand doesn't lay back like shooting a basketball to shoot the racket face to the ball, if it does you are doing the waiter's tray thing. The hand instead waves back and forth to wind up and then throw the racket in the same manner as if pitching a baseball. The third source of serve weakness for most tennis aficionados, the first being shifting your body weight backwards when the arms go down together and up together, second bending the racket arm too soon, is opening the racket face way early. You need to keep the racket on edge for as long as possible, and you open the racket face only right at the end.

Another variable to learning this form is the commonly known praying mantis position of the racket arm as it's rising. Here the wrist is bent so the racket hangs a bit in an opposite direction to effectively kill the possibility of the racket laying backwards in the hand (cuz of momentum) and the hand opening up. This bent-wrist position is evident everywhere. If you focus on moving your hand down and up instead of moving the racket you can achieve the bent-wrist position. Think of your hand/wrist being pulled up by a string like on a marionette, it helps keep your wrist loose and flexible in order to avoid the waiter's tray and keep the racket on edge.

Another variable to learning this form is the commonly known praying mantis position of the racket arm as it's rising. Here the wrist is bent so the racket hangs a bit in an opposite direction to effectively kill the possibility of the racket laying backwards in the hand (cuz of momentum) and the hand opening up. This bent-wrist position is evident everywhere. If you focus on moving your hand down and up instead of moving the racket you can achieve the bent-wrist position. Think of your hand/wrist being pulled up by a string like on a marionette, it helps keep your wrist loose and flexible in order to avoid the waiter's tray and keep the racket on edge. Exactly as with a forehand groundstroke the serve stroke uses a loop when the stroke prepares and then swings (down and up) at the ball. This also implies two beats to the stroke, it is not all one continuous motion at the same speed. A groundie starts the loop "racket up" and the racket moves behind you while still held up; a serve starts its loop "racket down and up" (#1 in photos) and the racket creeps to behind your head but the arm does not fully bend or cock to throw. A groundie hits the second beat by dropping

Exactly as with a forehand groundstroke the serve stroke uses a loop when the stroke prepares and then swings (down and up) at the ball. This also implies two beats to the stroke, it is not all one continuous motion at the same speed. A groundie starts the loop "racket up" and the racket moves behind you while still held up; a serve starts its loop "racket down and up" (#1 in photos) and the racket creeps to behind your head but the arm does not fully bend or cock to throw. A groundie hits the second beat by dropping

With the racket down the back, how does it go up to the ball? Butt cap first. And like a rocket taking off. The body doesn't go up like a rocket, the racket does. Sure, fundamentalist interpretation would say it's a myth the racket goes up butt cap first since you don't hit the ball with the butt cap and photos show the butt cap is turning down on the racket's way up to the ball. But while strictly correct I don't first focus on flipping the racket face up to the ball, I focus on the butt cap and the racket goes up on edge.

With the racket down the back, how does it go up to the ball? Butt cap first. And like a rocket taking off. The body doesn't go up like a rocket, the racket does. Sure, fundamentalist interpretation would say it's a myth the racket goes up butt cap first since you don't hit the ball with the butt cap and photos show the butt cap is turning down on the racket's way up to the ball. But while strictly correct I don't first focus on flipping the racket face up to the ball, I focus on the butt cap and the racket goes up on edge.